A secondary health crisis: undiagnosed conditions due to deferred care

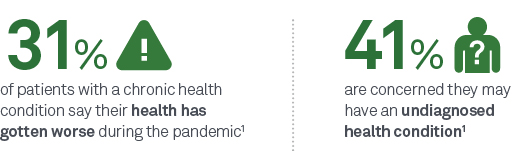

With 60% of Americans deferring care during the COVID-19 pandemic,1 many patients are finally returning to care. But now, you may be seeing them when they’re sicker or at greater risk for undiagnosed conditions.

The collateral negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on other health issues are staggering—and the impact may be felt for a generation.

- 64% decrease in diagnostic tests for heart disease2

- 46% decrease in new cancer diagnoses3

- 53% decrease in reported cases of chlamydia, and 33% decrease in reported cases of gonorrhea4

- 70% decrease in new type 2 diabetes diagnoses5

- 28% increase in drug overdose deaths6

"We are worried about swapping one public health emergency for another public health emergency, and we don’t want to let that happen.”

— Norman E “Ned” Sharpless, MD, Director of the National Cancer Institute (NCI)7

COVID-19’s long-term impact on patient health: what to watch for

While many patients with COVID-19 recover within a few weeks,8-10 some of those who have recovered face several potentially significant health challenges postinfection.

of patients may experience post–COVID-19 conditions such as long-haul COVID11

COVID-19 patients could be left with chronic health problems postinfection12

of asymptomatic patients developed long-haul COVID9

Post–COVID-19 conditions are a wide range of new, returning, or ongoing health symptoms patients can experience more than 4 weeks postinfection, often referred to as long-haul COVID.

Long-haul COVID could impact any patient who had COVID-19, including those who were asymptomatic during the active infection period.8-10

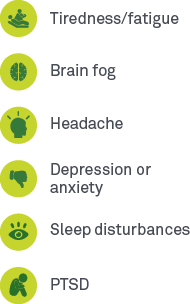

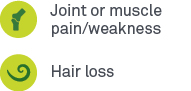

Long-haul COVID symptoms commonly reported include10,13:

Neurology:

Autoimmune:

Cardiology:

Respiratory:

Renal:

Supporting HCPs in uncovering undiagnosed conditions with targeted lab testing

Now, more than ever, laboratory testing is one critical tool to illuminate a care pathway forward for you and your patients in the COVID-19 era. Whether your patients are presenting with new, undiagnosed conditions due to deferred care or a SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection, Quest Diagnostics provides the right testing solutions for you to consider to help them get their health back on track. Below are some of the areas you may want to monitor your patients for:

Primary care visits decreased by 21% during the pandemic.14 The primary care visit is a critical touchpoint for baseline/routine lab testing, annual screenings, and to identify patients who may need additional, specialty care and tests for new or worsening conditions.

Routine lab testing, particularly if deferred during the pandemic, is an important tool for developing a baseline understanding of your patient’s health. A current picture of your patient’s health can help you make more informed decisions about their care pathway as they return to care. In addition, routine lab testing provides valuable insights that can be used to measure the impact of COVID-19 on a patient’s overall health, should they become infected.

Healthcare providers may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients. Below are some of the tests practitioners may find helpful in developing a better understanding of their patients’ current health status:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC), includes differential and platelets

- Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP)

- Basic Metabolic Panel

- Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)

- Lipid Panel, Standard

- Vitamin D, 25-Hydroxy, Total, Immunoassay

- SARS-CoV-2 Serology (COVID-19) Antibodies (IgG, IgM), Immunoassay

- ANA Screen,IFA, with Reflex to Titer and Pattern

- ANA Screen,IFA,Reflex Titer/Pattern,Reflex Mplx 11 Ab Cascade with IdentRA®a

For patients with preexisting thrombotic conditions:

For patients presenting within clinical symptoms consistent with a possible autoimmune disease:

a Panel components may be ordered separately.

A study showed that deferred care led to a decrease in 1 hospital's Hepatitis C (HCV) testing by 50%,16 and a reduction in new HCV diagnoses by more than 60%.16 As symptoms can be slow to manifest, many patients are unaware they have the disease—reinforcing the importance of laboratory testing to obtain an accurate diagnosis and initiate treatment before the disease progresses.

For patients recovering from a SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection, some conditions to consider monitoring for include autoimmune, respiratory/secondary infections, and tuberculosis.

As patients post–SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection commonly report varying stages of fatigue and muscle weakness,17 detecting inflammation of the muscles and identifying the cause can help inform appropriate treatment plans.

People who are ill with tuberculosis (TB) and other respiratory infectious diseases, such as SARS-CoV-2, influenza A/B, and RSV, often present with overlapping symptoms.

Throughout the year, there are high incidences of influenza-like respiratory issues like allergies and asthma across the country, according to the CDC.18,19 Asthma patients might be at an increased risk from COVID-19.20 Quest continues to offer influenza, RSV, and allergy testing, including influenza A/B + RSV to differentially diagnose influenza A/B and RSV, as well as ImmunoCAP® to diagnose respiratory allergies.

While experience with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection in tuberculosis (TB) patients remains limited, it is anticipated that people ill with both TB and COVID-19 may have poorer treatment outcomes, especially if the TB treatment is interrupted.21 Quest offers convenient screening via TB blood testing, providing results after just 1 patient encounter.

HCPs may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients. Below are some of the tests HCPs may find helpful in developing a better understanding of their patients’ current health status.

- Hepatitis C Viral RNA, Quantitative, Real-Time PCR

- ANA Screen,IFA,Reflex Titer/Pattern, Reflex Mplx 11 Ab Cascade with IdentRA®a

- Anti-nuclear Antibody (ANA) Screen, IFA, with Reflex to Titer and Pattern and Reflex to Multiplex 11 Antibody Cascade

- SARS-CoV-2 RNA (COVID-19) and Influenza A and B, Qualitative NAATb

- SARS-CoV-2 RNA (COVID-19) and Respiratory Viral Panel, Qualitative NAATb

- SARS-CoV-2 RNA (COVID-19) and Respiratory Pathogen Panel, Qualitative NAATb

- SARS-CoV-2 RNA (COVID-19), Qualitative NAATb

- Influenza A and B RNA, Qualitative Real-Time PCR

- Influenza A and B and RSV RNA, Qualitative, Real-Time RT-PCR

- Respiratory Viral Panel (RVP), PCR

- Respiratory Pathogen Panel (RPP)

- Allergen (IgG), ImmunoCAP®, House Dust Greer

- QuantiFERON®-TB Gold Plus, 1 Tube

- T-SPOT®.TB

a Panel components may be ordered separately.

b This test could be considered where there is concern that the patient has developed COVID-19, has tested negative twice after being diagnosed with COVID-19 for purposes of determining recovery, or has relapsed or been re-infected. This test may be needed in these situations in order to determine an accurate diagnosis.

A dramatic rise in US adult obesity rates22 may be a contributing factor in increased incidences of key chronic disease conditions, including diabetes.23 As diabetes progresses, cardiovascular disease risk increases.24 Uncovering pre-existing conditions that may place patients at increased risk for these chronic diseases is critical, as certain lifestyle changes, including weight loss, may help prevent additional disease complications and progression.22

For patients with obesity, key tests including lipid panels, ApoB, insulin resistance panel, and HbA1c can help in identifying possible chronic disease risk.

Cardiovascular risk assessment includes lipid values, inflammation, lipoprotein subfractions, and apolipoproteins. These tests may provide deeper insights into the residual risk of your patients.

Viral infections may lead to an increase in risk for heart attacks. Uncovering heart attack risks that may be triggered by the COVID-19 virus is important to patient health. ADMA, Lp-PLA2, and MPO tests offer the ability to define current vascular inflammation of a given patient.

Vitamin D deficiency is associated with muscle weakness, impaired muscle performance, and loss of type II fibers.25

HCPs may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients. Below are some of the tests HCPs may find helpful in developing a better understanding of their patients’ current health status.

There is a growing body of evidence of a high prevalence of blood clots, strokes, heart attacks, and organ failures among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19).26 Consider monitoring platelet count, PT/aPTT, D-Dimer, and fibrinogen. Continued monitoring of patients post-discharge is suggested for patients on extended prophylaxis.27

HCPs may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients. Below are some of the tests HCPs may find helpful in developing a better understanding of their patients’ current health status.

A recent study in JAMA Network Open found a 46% drop in the detection of all cancers3, suggesting many patients are deferring care and placing their health at risk. Colorectal cancer and breast cancer saw an even bigger drop in new diagnoses, at more than 49% and 52%, respectively.3

Resuming age-based screenings is imperative to diagnose cancer at an earlier stage, when patients may have more treatment options and a more favorable outcome. Quest Advanced™ Oncology offers a comprehensive menu of oncology tests that span the full spectrum of cancer care and management.

HCPs may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients, including age-based cancer screenings.

Post–SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection, neurological complications that may arise could include encephalitis, myasthenia gravis (MG), and Guillain-Barré syndrome. A recent study of COVID-19 survivors found that 34% of patients were diagnosed with neurological or mental health disorders 6 months post-infection.28

Key, targeted panels aid in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic syndromes and autoimmune encephalopathies and related conditions. As symptoms commonly overlap across multiple conditions, identification of autoantibody specificity may allow syndromic classification and assist in diagnosis and management.

As patients may experience changes in muscular function and weakness post–SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection, appropriately identifying antibodies that are present in neuromuscular syndromes, such as MG and Guillain-Barré syndrome, may help inform an appropriate treatment path.

HCPs may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients. Below are some of the tests HCPs may find helpful in developing a better understanding of their patients’ current health status.

38% of women delayed routine medical care and testing during the COVID-19 pandemic.29 As a result, screening rates for cervical cancer30 and STIs31 among women ages 18+ were particularly impacted.

With a 94% decrease in cervical cancer screenings from pre-pandemic levels,30 researchers expect the delays in cancer screenings will result in increased diagnoses of advanced cancers and deaths.32

During the COVID-19 pandemic, STI services were disrupted, suggesting an increase in syndromic testing and missed asymptomatic cases.31 New research shows 26% and 17% estimated cases of chlamydia and gonorrhea, respectively, were missed during the pandemic.31

Undiagnosed cases of STIs or cervical cancer may lead to long-term health effects, including infertility33 and greater risk of death.34 STIs31 and early stage cervical cancer35 are often asymptomatic, making a return to routine screening more critical than ever to help women get their health back on track.

HCPs may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients. Below are some of the tests HCPs may find helpful in developing a better understanding of their patients’ current health status.

The negative collateral damage from COVID-19 is evident in the drug epidemic. The convergence of the two crises is responsible for the largest number of overdose deaths—87,000—ever recorded in a 12-month period.6

The toll COVID-19 has taken on mental health cannot be understated. With a 31% increase in US adults reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression during the pandemic,36 access to controlled medications may be an important treatment option.

An appropriate drug monitoring protocol can help provide clinicians with insights into multiple forms of misuse, including substance use, dangerous drug combinations, and medication noncompliance. Drug monitoring can help provide patients who need access to controlled medications an important treatment option, while helping to keep you, your patients, and your community safe.

Quest Diagnostics clinical drug monitoring services include an extensive menu for prescription pain medications, other controlled substances, and illicit drugs.

HCPs may consider a variety of testing approaches based on the needs of individual patients. Quest Diagnostics offers drug testing for nearly every metabolite to help HCPs develop a better understanding of their patients’ current health status.

Helping you manage deferred testing and care

The twindemic of COVID-19 and seasonal influenza

COVID-19 and colorectal cancer: a crisis in the making

Post–COVID-19 infection and neurology complications

Heart disease prevention in women: identifying risk and the role of the OB/GYN

Meeting the needs of fertility patients during COVID-19

A clinical view on diagnostic strategies from the AAFP for sexually transmitted infections

Clinical conversation: drug monitoring & patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic

Medication adherence: challenges during COVID-19

Drug misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic

Influenza A and B and SARS-CoV-2 panel test information

- This test has not been FDA cleared or approved;

- This test has been authorized by FDA under an EUA for use by authorized laboratories;

- This test has been authorized only for the simultaneous qualitative detection and differentiation of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2, influenza A virus, and influenza B virus, and not for any other viruses or pathogens; and

- This test is only authorized for the duration of the declaration that circumstances exist justifying the authorization of emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for detection and/or diagnosis of COVID-19 under Section 564(b)(1) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3(b)(1), unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

IgG antibody test and molecular test information

- The antibody tests and the molecular tests (together “All tests”) have not been FDA cleared or approved;

- All tests have been authorized by FDA under EUAs for use by authorized laboratories;

- The antibody tests have been authorized only for the detection of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, not for any other viruses or pathogens;

- The molecular tests have been authorized only for the detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2, not for any other viruses or pathogens; and,

- All tests are only authorized for the duration of the declaration that circumstances exist justifying the authorization of emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for detection and/or diagnosis of COVID-19 under Section 564(b)(1) of the Act, 21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3(b)(1), unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

IgG and IgM serology test information

The IgG and IgM antibody tests are intended for use as an aid in identifying individuals with an adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2, indicating recent or prior infection. Results are for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. IgG and IgM antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 are generally detectable in blood several days after initial infection, although the duration of time antibodies are present post-infection is not well characterized.

At this time, it is unknown for how long antibodies persist following infection and if the presence of antibodies confers protective immunity.

Individuals may have detectable virus present for several weeks following seroconversion. Negative results do not preclude acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. If acute infection is suspected, molecular testing for SARS-CoV-2 is necessary. The tests should not be used to diagnose acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. False positive results for the test may occur due to cross-reactivity from pre-existing antibodies or other possible causes. The sensitivity of the IgM test early after infection is unknown. Due to the risk of false positive results, confirmation of positive results should be considered using a second, different IgM assay or an IgG assay. Samples should only be tested for IgM from individuals with 15 days to 30 days post symptom onset. SARS-CoV-2 antibody negative samples collected 15 days or more post symptom onset should be reflexed to a test that detects and reports SARS-CoV-2 IgG.

IgM serology test information

- This test has not been FDA cleared or approved;

- This test has been authorized by FDA under an EUA for use by authorized laboratories;

- This test has been authorized only for the presence of IgM antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, not for any other viruses or pathogens; and

- This test is only authorized for the duration of the declaration that circumstances exist justifying the authorization of emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for detection and/or diagnosis of COVID-19 under Section 564(b)(1) of the Act, 21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3(b)(1), unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

References

- New Quest Diagnostics Health Trends™ survey reveals COVID-19 testing hesitancy among Americans, with 3 of 4 avoiding a test when they believed they needed one. Quest Diagnostics. News release. December 9, 2020. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://newsroom.questdiagnostics.com/2020-12-09-New-Quest-Diagnostics-Health-Trends-TM-Survey-Reveals-COVID-19-Testing-Hesitancy-Among-Americans-With-3-of-4-Avoiding-a-Test-When-They-Believed-They-Needed-One

- Einstein AJ, Shaw LJ, Hirschfeld C, et al. International impact of COVID-19 on the diagnosis of heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(2):173-185. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.054

- Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, Fesko Y. Changes in the number of US patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2017267. Accessed August 3, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17267

- Stulpin, C. Pandemic-related declines in testing, 'sexual distancing' cause dip in reported STDs. Infectious Disease News. September 15, 2020. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.healio.com/news/infectious-disease/20200915/pandemicrelated-declines-in-testing-sexual-distancing-cause-dip-in-reported-stds

- Carr MJ, Wright AK, Leelarathna L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on diagnoses, monitoring and mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: a UK-wide cohort study involving 14 million people in primary care. medRxiv. Epub February 14, 2021. doi:10.1101/2020.10.25.20200675

- CDC. Vital statistics rapid release. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Updated April 14, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- Cavallo J. How delays in screening and early cancer diagnosis amid the COVID-19 pandemic may result in increased cancer mortality. The ASCO Post. Published September 10, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://ascopost.com/issues/september-10-2020/how-delays-in-screening-and-early-cancer-diagnosis-amid-the-covid-19-pandemic-may-result-in-increased-cancer-mortality/

- Berg S. COVID long-haulers: questions patients have about symptoms. American Medical Association. Epub April 15, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-long-haulers-questions-patients-have-about-symptoms

- FAIR Health, Inc. A detailed study of patients with long-haul COVID: an analysis of private healthcare claims FairHealth.com. Published June 15, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/A%20Detailed%20Study%20of%20Patients%20with%20Long-Haul%20COVID--An%20Analysis%20of%20Private%20Healthcare%20Claims--A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

- CDC. Post-COVID conditions. Updated April 8, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects.html

- Carbajal E. Emerging trends among COVID-19 long-haulers: 6 physicians weigh in. Becker's Hospital Review. Published April 16, 2021. Accessed August 18, 2021. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/public-health/emerging-trends-among-covid-19-long-haulers-6-physicians-weigh-in.html

- Goodman B. CDC to issue guidelines as long-haul COVID numbers rise. WebMD. Published April 28, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2021. https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20210429/cdc-to-issue-guidelines-as-long-haul-covid-numbers-rise

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):601-615. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

- Alexander GC, Tajanlangit M, Heyward J. Use and content of primary care office-based vs telemedicine care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e.2021476. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21476

- CDC. Assessment and testing. Evaluating and caring for patients with post-COVID conditions: interim guidance. Updated June 14, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-assessment-testing.html

- Sperring H, Ruiz-Mercado G, Schechter-Perkins EM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ambulatory Hepatitis C testing. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2020; doi: 10.1177/2150132720969554

- Cortinovis M, Perico N, Remuzzi G. Long-term follow-up of recovered patients with COVID-19. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):173-175. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00039-8

- CDC. National Center for Health Statistics. Asthma. Updated April 14, 2021. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm

- CDC. National Center for Health Statistics. Allergies and Hay Fever. Updated March 1, 2021. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/allergies.htm

- CDC. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). People with certain medical conditions. Updated April 29, 2021. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

- WHO. Q&A: tuberculosis and COVID-19. Published May 11, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/tuberculosis-and-the-covid-19- pandemic

- State of Childhood Obesity. National obesity monitor. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/monitor/

- CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- Khaw KT, Wareham N, Luben R, et al. Glycated haemoglobin, diabetes, and mortality in men in Norfolk cohort of European prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition (EPIC-Norfolk). BMJ. 2001;322(7277):15-18. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7277.15

- Beaudart C, Buckinx F, Rabenda V, et al. The effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass, and muscle power: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(11):4336‐ 4345. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1742

- Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417-1418. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5

- Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950-2973. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031

- Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236,379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):416-427. doi: /10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5

- Frederiken B, Ranji U, Salganicoff A, Long M. Women’s experiences with health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the KFF women’s health survey. KFF.org. Published March 22, 2021, Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/womens-experiences-with-health-care-during-the-covid-19-pandemicfindings-from-the-kff-womens-health-survey/

- Printz C. Cancer screenings decline significantly during pandemic. Cancer. 2020; 126(17): 3894–3895. doi:10.1002/cncr.33128

- Pinto CN, Niles JK, Kaufman HW, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on STI testing. Am J Prevent Med. TBD.

- Castanon A, Rebolj M, Burger EM, et al. Cervical screening during the COVID-19 pandemic: optimizing recovery strategies. Lancet. Published April 30, 2021. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00078-5

- CDC. STDs & infertility. Updated March 29, 2021. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/infertility/default.htm

- American Cancer Society. Survival rates for cervical cancer. Updated February 2, 2021. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- Wipperman J, Neil T, William T. Cervical cancer: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2018; 97(7):449-454. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/0401/p449.html

- Abbott A. COVID’s mental-health toll: how scientists are tracking a surge in depression. Nature. Published February 3, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00175-z

Test codes may vary by location. Please contact your local laboratory for more information.

The CPT® codes provided are based on American Medical Association guidelines and are for informational purposes only. CPT coding is the sole responsibility of the billing party. Please direct any questions regarding coding to the payer being billed.

Image content features models and is intended for illustrative purposes only.