Malignant Melanoma: Diagnosis, Laboratory Testing, and Management

Malignant melanoma (melanoma) is a cancer of melanocytes that most often occurs on the skin—primarily due to excess sun exposure.1 The American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates that in 2022 about 100,000 new cases of melanoma will be diagnosed and about 7,500 people will die from the disease.2 Melanoma is more than 20 times more common in White than in Black Americans. Overall, the estimated lifetime risk for melanoma is about 2.6% (1 in 38) for White, 0.6% (1 in 167) for Hispanic, and 0.1% (1 in 1,000) for Black persons.2

When melanoma is diagnosed early (localized disease; the cancer has not spread beyond the region of skin where it started), the 5-year relative survival rate approaches 100%.3 However, melanoma is an aggressive malignancy, with early regional and distant metastasis, and the 5-year survival rate in patients with distant metastases is only about 16%.3

This article will discuss the causes, risk factors, diagnosis, classification, management, and prevention of melanoma, including the importance of early detection.

Malignant melanoma: causes, risk factors, and prevention

Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light (eg, sunlight, indoor tanning) is the most important risk factor for melanoma.4 UV exposure results in genetic alterations in melanocytes, which in turn lead to malignant transformation.5 Fair-skinned and light-haired persons living in high sun-exposure environments have the greatest risk,5 but malignant melanoma can also affect persons with darker skin (see Sidebar).6 Other risk factors include sunburns, the presence of melanocytic or dysplastic nevi, and a personal history or family history of cutaneous melanoma (see Sidebar).4,5,7 Hereditary gene variants may be a reason for the increased risk among individuals with a family history of melanoma.7-10 Notably, melanoma can also occur on skin that is shielded from sun exposure (see Sidebar).11

Melanoma is one of the more preventable forms of cancer. Counseling in primary care settings about modified behaviors, including decreased intentional tanning, leads to reduced risk of melanoma.12 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that clinicians counsel patients with fair skin who are 10 to 24 years old to minimize their exposure to sunlight and artificial UV light.13 The ACS recommends4,14

- Avoiding prolonged exposure to midday sun

- Wearing a wide-brimmed hat

- Wearing tightly woven clothing that covers arms and legs

- Wearing sunglasses that block both UVA and UVB rays

- Using a broad-spectrum sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher

- Avoiding indoor tanning

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of melanoma combines visual screening, biopsy, and histological examination as discussed below.

Visual screening

Pigmented nevi (moles) are benign proliferations of melanocytes in the skin, and typically do not change in size or disappear over time.15 However, approximately 33% of melanomas are derived from pigmented nevi.15 Visual screening during a total body skin examination (TBSE) is an easy and effective way to detect new or changing moles—patients should be encouraged to examine themselves each month.16,17 A monthly TBSE is especially important for people of color in whom skin cancer, including melanoma, is often diagnosed at a late stage (see Sidebar).6

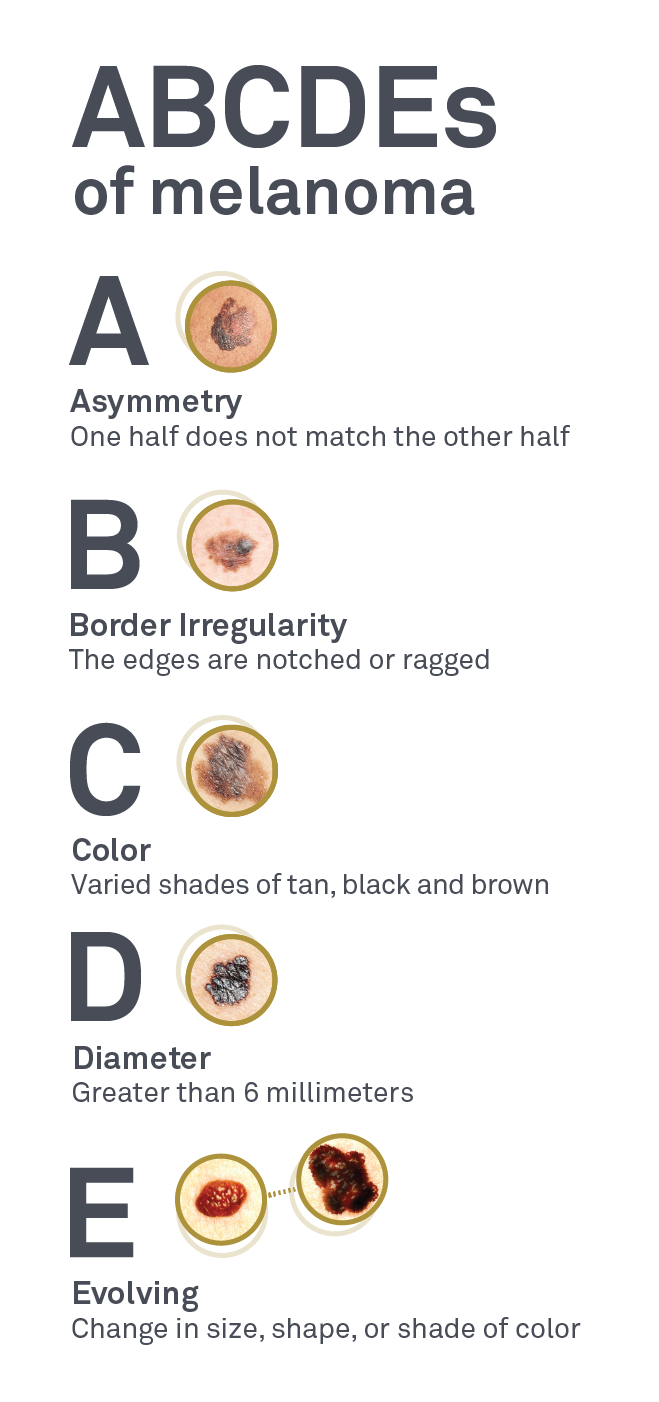

Characteristic clinical features of pigmented lesions can suggest the presence of melanoma and are represented by the mnemonic “ABCDEs” of melanoma: (A) asymmetry; (B) border irregularity; (C) color variation; (D) diameter >6 mm; and (E) evolving or changing appearance.16,17

Dermatoscopy involves the use of a handheld instrument that provides 10× magnification and illuminates skin such that light reflection from the surface is minimized. The tool is useful for examining pigmented lesions, identifying characteristics suggestive of melanoma, and determining the extent of a biopsy.18,19

Biopsy

While physical characteristics of a pigmented lesion can raise the suspicion of melanoma, definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy of the lesion and examination of the tissue specimen by an experienced dermatopathologist.20 American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines indicate that a biopsy can be incisional (removing part of the lesion) or excisional (removing the entire lesion).20 For lesions with a high suspicion of being melanoma, AAD recommends an excisional biopsy with 1- to 3-mm margins and sufficient depth to ensure the lesion is not transected.20

Biopsy can be performed by surgical excision, punch excision, or shave removal to a depth below the suspected plane of the lesion.20 Patient age and sex, anatomic location, size of the lesions, and biopsy technique are important information to include with the biopsy tissue specimen.20 Other information, such as dermatoscopic features and photographs, can also help dermatopathologists evaluate the tissue specimen.

Histologic examination of tissue specimen

Melanoma is definitively diagnosed by histopathologic examination of the tissue specimen to assess histologic type and other tumor characteristics.21,22 Tumor thickness (Breslow thickness), ulceration, dermal mitotic rate, peripheral and deep margin status (positive vs negative), anatomic level of invasion (Clark level), and microsatellitosis should be examined and included in the pathology report.20 Other features useful for diagnosis include lymphovascular invasion, neurotropism, regression, T-stage, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, and vertical growth phase.20

While the aforementioned characteristics may be associated with prognosis and outcome, 3 histologic features are the most important20:

- Maximum Breslow thickness, measured from the granular of the overlying epidermis or base of superficial ulceration to the deepest malignant cells invading the dermis

- Presence or absence of microscopic ulceration, defined as tumor-induced full-thickness loss of epidermis with subjacent dermal tumor and reactive dermal changes

- Mitotic rate: the number of dermal mitoses per mm2; a mitotic rate ≥1 mitosis/mm2 is independently associated with worse disease-specific outcome

Staging and prognosis

Melanomas are staged based on the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging system.23 In brief, stages range from T0 (Stage 0: melanoma in situ; melanoma cells are found only in the outer layer of skin or epidermis) to stage IV (distant metastasis), with numerous substages based on clinical and histopathological characteristics. Stage 0 is associated with a relative 5-year survival rate of 100%; stage I-II, 97.6%; stage III (regional metastasis), 60.3%; and stage IV, 16.2%.3

Molecular characterization and management

Melanomas develop as a result of abnormalities in melanocyte genetic pathways that initiate cell proliferation and cessation of apoptosis as a normal response to DNA damage.15 Gene variants are the main driving force in this process; those of BRAF and NRAS are the most commonly associated with melanoma.15 Many gene variants are associated with the development, progression, and prognosis of melanoma; however, targeted therapies which can improve outcomes have been developed for only a small number of variants (eg, BRAF).24

Skin cancer in people of color

People of color (African, Asian, Latino, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Native American descent) can develop skin cancer—acral melanoma is most prevalent.6 Notably, skin cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage in people of color.6 The AAD recommends people of color perform a monthly TBSE, including areas that do not get any sun such as the bottoms of the feet and inside the mouth, to look for 6

- Dark spots, growths, or darker patches of skin that are growing, bleeding, or changing in any way

- Sores that don’t heal, or heal and return (especially if the sore appears in a scar or on skin that was injured in the past)

- Patches of skin that feel rough and dry

- Dark lines underneath or around a fingernail or toenail

Risk factors for melanoma

Risk factors for melanoma include4,5,7

- Age: 35 to 75 years

- Personal history of skin cancer

- Family history of skin cancer

- Light skin

- Blond or red hair

- More than 40 moles

- 2 or more atypical moles

- Many freckles

- Sun-damaged skin

- History of blistering sunburn·

- History of indoor tanning

World Health Organization (WHO) melanoma classification

Classification of melanoma is based on gross clinical and pathological features, including their growth pattern and location on the body. In addition, the WHO classifies melanoma based on the presence or absence of sun exposure, including melanoma arising on skin that is11

- Sun-shielded

- Sun-exposed with

- Low-chronic sun damage

- High-chronic sun damage

Different degrees of sun exposure are associated with the different histological subtypes of melanoma and different genetic variants (eg, BRAF variants are associated with low-chronic sun damage, while NRAS variants are common in high-chronic sun damage melanoma).11 Thus, WHO classification links pathogenesis with genetic drivers, and assists in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning.11

How the Laboratory Can Help

Dermpath Diagnostics, a Quest Diagnostics company, offers a comprehensive test menu for dermatological needs, including testing of skin biopsies with analysis performed by board-certified dermatopathologists. In addition to tests for heredity and tumor burden, Dermpath offers BRAF/c-KIT testing for patients with metastatic melanoma.5 Dermpath and Quest also offer companion diagnostic tests including Melanoma, BRAF V600 Mutation, Cobas® and Melanoma, BRAF V600E and V600K Mutation Analysis, THxID™.5 Together with microsatellite instability and tumor mutation burden testing, these tests help identify candidates for targeted immune therapy.25 Quest also offers multigene panels to identify hereditary gene variants associated with various cancers, including hereditary variants associated with malignant melanoma. For a comprehensive description of tests and panels, including gene panels such as MELANOMASEQ (a melanoma-specific solid tumor panel for identifying gene variants and clinical choices for patients with advanced-stage melanoma), see

The website Spot the Spot™ (SpottheSpot.org) has also been developed by Dermpath Diagnostics to educate patients on how to protect and inspect their skin to help prevent and identify skin cancer and other skin-related conditions.

Note: Dermpath and Quest contract independently with insurance companies.

References

- Melanoma treatment (PDQ®)-health professional version. National Cancer Institute. Updated July 23, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/hp/melanoma-treatment-pdq

- Key statistics for melanoma skin cancer. American Cancer Society. Revised January 12, 2022. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- Five-year survival rates. National Cancer Institute: SEER Training Modules. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/melanoma/intro/survival.html

- Risk factors for melanoma skin cancer. American Cancer Society. Revised August 14, 2019. Accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

- Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):971-984. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31559-9

- Skin cancer in people of color. American Academy of Dermatology. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/types/common/melanoma/skin-color

- Soura E, Eliades PJ, Shannon K, et al. Hereditary melanoma: update on syndromes and management: genetics of familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):395-407. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.038

- Ribero S, Glass D, Bataille V. Genetic epidemiology of melanoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26(4):335-339. doi:10.1684/ejd.2016.2787

- Read J, Wadt KAW, Hayward NK. Melanoma genetics. J Med Genet. 2016;53(1):1-14. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103150

- Toussi A, Mans N, Welborn J, et al. Germline mutations predisposing to melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47(7):606-616. doi:10.1111/cup.13689

- Elder DE, Bastian BC, Cree IA, et al. The 2018 World Health Organization classification of cutaneous, mucosal, and uveal melanoma: detailed analysis of 9 distinct subtypes defined by their evolutionary pathway. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144(4):500-522. doi:10.5858/arpa.2019-0561-RA

- Skin cancer prevention progress report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed April 28, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/what_cdc_is_doing/progress_report.htm

- Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4(1):13-37. doi:10.2217/mmt-2016-0022

- How do I protect myself from ultraviolet (UV) rays? American Cancer Society. Reviewed July 23, 2019. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/skin-cancer/prevention-and-early-detection/uv-protection.html

- Strashilov S, Yordanov A. Aetiology and pathogenesis of cutaneous melanoma: current concepts and advances. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6395. doi:10.3390/ijms22126395

- Detect skin cancer: how to perform a skin self-exam. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/check-skin

- What to look for: the ABCDEs of melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/at-risk/abcdes

- Zalaudek I, Lallas A, Moscarella E, et al. The dermatologist's stethoscope-traditional and new applications of dermoscopy. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3(2):67-71. doi:10.5826/dpc.0302a11

- Marghoob NG, Liopyris K, Jaimes N. Dermoscopy: a review of the structures that facilitate melanoma detection. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(6):380-390. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2019.067

- Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):208-250. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.055

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Cutaneous Melanoma. Version 2.2021. Published February 19, 2021. https://www.nccn.org

- Wright FC, Souter LH, Kellett S, et al. Primary excision margins, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and completion lymph node dissection in cutaneous melanoma: a clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(4):541-550. doi:10.3747/co.26.4885

- Keung EZ, Gershenwald JE. The eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging system: implications for melanoma treatment and care. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18(8):775-784. doi:10.1080/14737140.2018.1489246

- Shaughnessy M, Klebanov N, Tsao H. Clinical and therapeutic implications of melanoma genomics. J Transl Genet Genom. 2018;2:14. doi:10.20517/jtgg.2018.25

- Leonardi GC, Falzone L, Salemi R, et al. Cutaneous melanoma: from pathogenesis to therapy (review). Int J Oncol. 2018;52(4):1071-1080. doi:10.3892/ijo.2018.4287

Content reviewed 5/2022